Dimensions of blades

Pavel Bolf

I recently completed a job that was a bit different from the usual ones. The client supplied his blade, I was to polish it and fit it with a koshirae (set). The blade was roughly half the size of my swords in terms of massiveness. Similarly, most of the swords, from the serial production of various companies, often have subtle blades that do not match the parameters of a new sword.

This is probably due to the fact that antique swords, which are often very "tired", are used as a template for the production of the blade. Therefore, in the following lines we will describe the differences between old and new blades, more precisely used, repeatedly repaired and newly made swords.

It is probably impossible to describe with millimetre precision what the dimensions of the newly made sword should be. Certainly the type of blade (historical period) must also be taken into account. Here, there are considerable differences in shape, which were influenced by the way the sword was used. The description is therefore rather indicative.

Width and thickness of the blade.

The width at the tang (nakago) between the tips of the blade fit (hamachi) and the spine fit (munemachi) is called motohaba, and the thickness is called motokassane. In the area in front of the tip (kissaki), the dimension between the back (mune) and the blade (ha) is sakihaba and the blade thickness is sakikassane. For the ratio between the dimensions at the tip and the fit in front of the nakago, the approximate rule is 70% at the tip to 100% machi. This applies to both dimensions, width and thickness (kassane). The blade therefore narrows towards the tip by about 30%.This rule is not a dogma. Some swordmakers, for example, make blades that have the same kassane along the entire length.

At present I usually make blades with the following dimensions. Length approx. 76 cm, motohaba 34 mm, sakihaba 25-27 mm, motokassane 8 mm, sakikassane 6-7 mm.

These dimensions are for commonly made swords at the upper maximum.

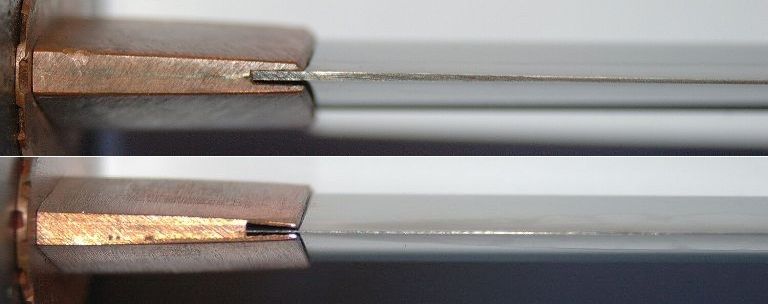

The height of the hamachi and monemachi mount is approx. 2.5 mm. This dimension is good to observe in antique blades. it is clearly visible here how the restoration of the blade resulted in lowering of both settings. The hamachi is often considerably lower than the munemachi, even though they are the same height on a newly made sword. The reason is simple. With use, the wear on the blade was much more pronounced than on the spine. If the blade underwent several major repairs, such as the removal of teeth after combat (hakobore), it happened that the hamachi disappeared completely and the blade line transitioned smoothly into the nakago. Of course, it was necessary for the hamon line to reach a sufficient height so that it was maintained at least at a minimum height along the entire length of the blade.

Ubuha

In order not to grind the hamachi too quickly, part of the blade in about the first fifth behind the hamachi is blunt, more precisely the blade is flat (about 1-2 mm) During the first repairs the blade is narrowed in the part near the tip (monouchi), the ubuha is also thinned but the hamachi is not reduced. After a few repairs the ubuha disappears and the blade is sharp along its entire length. However, the proportions of the dimensions have already changed in this state. Compared to the new blade, the modified blade is significantly narrower in the direction of the tip. It thus acquires a very elegant shape, in contrast to the more robust shape at the beginning of its career. The specific shape changes caused by the repairs are of course dependent on the degree and type of damage (e.g. the location of the broken teeth).

Hiraniku

It is a dimension indicating the curvature (bulge) of the area between the blade and the central rib (shinogi), or the blade and the edge of the spine in hira - zukuri blades. This area is ideally in the shape of a regular lens. The size of this dimension (niku) has a direct influence on the blade's characteristics. It influences the blade's ability to cut and resist tooth breakage. The flatter the hiranic, the narrower the wedge that the blade surfaces create, and thus the sharper the sword. On the other hand, however, the resistance of the blade to punctures is lower. On the other hand, with a massive hiraniku, the blade is more resistant, but the sharpness is not as pronounced as in the previous case. For a newly made sword, it depends on the manufacturer how the nick will be shaped. I decide according to the purpose for which the sword is intended. If the customer intends to use it for tameshigiri and chopping straw, the niku is usually less pronounced than on a blade with which he does not intend to do the chopping. From my point of view, it is somewhat unfortunate that a large number of those who practice various forms of Japanese swordsmanship prefer swords that are very light and very sharp. To make a 76 cm long blade with the parameters mentioned in the previous paragraphs, while weighing 800g, is actually to make an already tired blade with an almost flat hiraniko. If such a sword were to go through actual combat, where it would have to cut through pieces of armour and clash with other swords, it would probably be useless afterwards. Some mass-produced swords have no hiratic and the surfaces forming the blade are completely flat. The serrations on such a razor-sharp blade then break off even when chopping dry straw. However, polishing a flat surface is easier than polishing a pronounced lens, especially while maintaining shinogi. This is probably also the reason why this type of blade is chosen for some of these swords. Returning to the changes in shape by wear, however, a newly made sword has more hiranic than its repaired successor.

Hamon

The hamon is balanced on the newly made sword. It usually rises slightly at the hamachi, to continue at about the same height for a short distance until the mayachi (the last 20 cm or so of the blade), where it can rise slightly again. This description is just one of many possibilities and is chosen to make it easier to describe the subsequent wear. Some swordmakers, on the other hand, let the hamon drop in the monouche, presumably to reduce the risk of breaking the blade at its most stressed part. There are a number of other variations. In the above case, repeated resharpening of the blade reduces hardening in the monouche. At the end of its career, the height of the hamon decreases as a result of repairs. At the same time, changes in the shape of the tip also occur. If the very tip of the tip breaks, only the necessary correction of the shape is made (rounding of the fucture). Opinions on the original shape of the fucura vary. Some hold that the rounded shape of the fucura was created during the manufacturing process, while others prefer the opposite, i.e. through wear and tear. One type of kissaki (tip) is the kamatsu kissaki, where the line of the fukura is almost straight. This type exists in short (ko), medium (chu) and long (ó) variants. I personally believe that the shape of the sword tip was and is greatly influenced by the personal taste of each swordsmith. However, in any case, the tip area is the most beautiful and, from a manufacturing perspective, the most difficult part of the blade.

Mizukage

This effect, produced during hardening, is certainly worth mentioning. It appears as a shadow, directed obliquely upwards from the blade. It usually occurs before the beginning of the hamon line. The mizu kage (water shadow) is formed as a border of the blade plunging into the water. If the entire blade, including the nakago, is immersed in water during hardening, this effect does not occur. On some old swords, the hardening begins several centimetres beyond the hamachi, and it is often very clearly visible on these swords. If it occurs on a shortened blade, it is an indication that the blade has been re-hardened otherwise the hamon would continue into the nakago. Some sources refer to mizukage as a blemish on the blade. For repainted blades this is understandable, for original or new blades such a view is unfounded.

Shortening

There could have been several reasons for shortening the blade. In the course of Japanese history, several decrees or regulations were issued to regulate the length of swords. See the article by Jakub Zeman - Wakizashi (Fighters magazine 1-2 /2007). And then, of course, the personal reasons of the owner of the sword, for whom its too long blade may not have suited.

Shortening the blade was always done from the tang (nakago), never from the tip. In the case of shortening from the tip, the newly sharpened tip would be without a hamon line, and in the end actually destroyed the blade.

The shortening itself, therefore, represents the severing or cutting off of the necessary long back of the nakago, and the corresponding displacement of the hamachi and munemachi fitting.

If the shortened blade was signed by the maker, the signature (mei) was moved to the end of the nakago, or, in the case of a larger shortening, disappeared altogether. If the owner wanted to preserve the mei, the original signature could be cut out of the removed nakago remnant and inserted into the newly formed nakago (gaku mei). For blades signed in this way, there is a possibility that the inserted mei came from another (e.g. fire-damaged) sword, and was inserted into a blade of inferior quality in order to increase its price. In case of doubt, it is therefore advisable to study whether the mei matches the characteristics of the work of the signed swordsman.

Another option for preserving the mei is to trim the mei and turn it to the ura side of the nakago without completely separating it from the original blade (orikaeschi mei).

Shortened blades were not re-signed (by cutting), as each swordsmith's signature is authentic not only in appearance but also, for example, in typeface, placement of the signature, etc. In some cases, the blade is signed in gold or red lacquer, depending on whether the blade was described when it was shortened or whether the author was assigned to it by an expert after the fact.

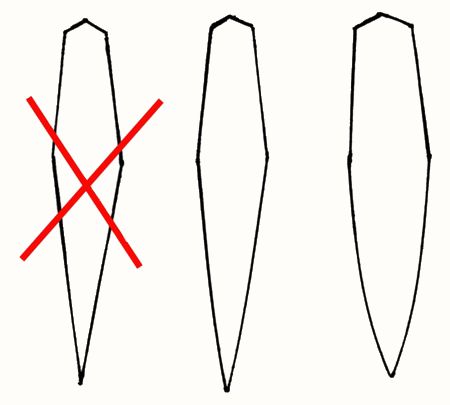

Satsumaage

This designation is given to a not very well known modification of broken blades. If the blade was broken, two repair options were offered. The first, sharpening a new point, gave rise to a weapon with an unbroken tip, i.e. functionally limited. However, this option is currently resorted to by collectors and dealers, as it will at least partially preserve the original character of the damaged sword. However, the value of such a blade is significantly reduced. The second option was to create a new blade by gradually lowering the spine line down to the blade. This created a blade with a crow's beak shaped tip (satsumaage). Although the original shape of the blade was completely changed, the hamon was passed through the tip and the blade was functionally complete. However, I believe that from the current perspective of sword collectors and restorers, in most cases such an intervention in the design would be unacceptable and was considered rather destructive. However, from the user's point of view it is undoubtedly about restoring the functionality of a (expensive) blade that would otherwise no longer be of use in combat.